Reproductions

13 December 2025 - 24 January 2026

Thursday - Saturday, 12.00 - 6.00pm

C A B I N E T

132 Tyers Street

London SE11 5HS

art@cabinet.uk.com

www.cabinet.uk.com

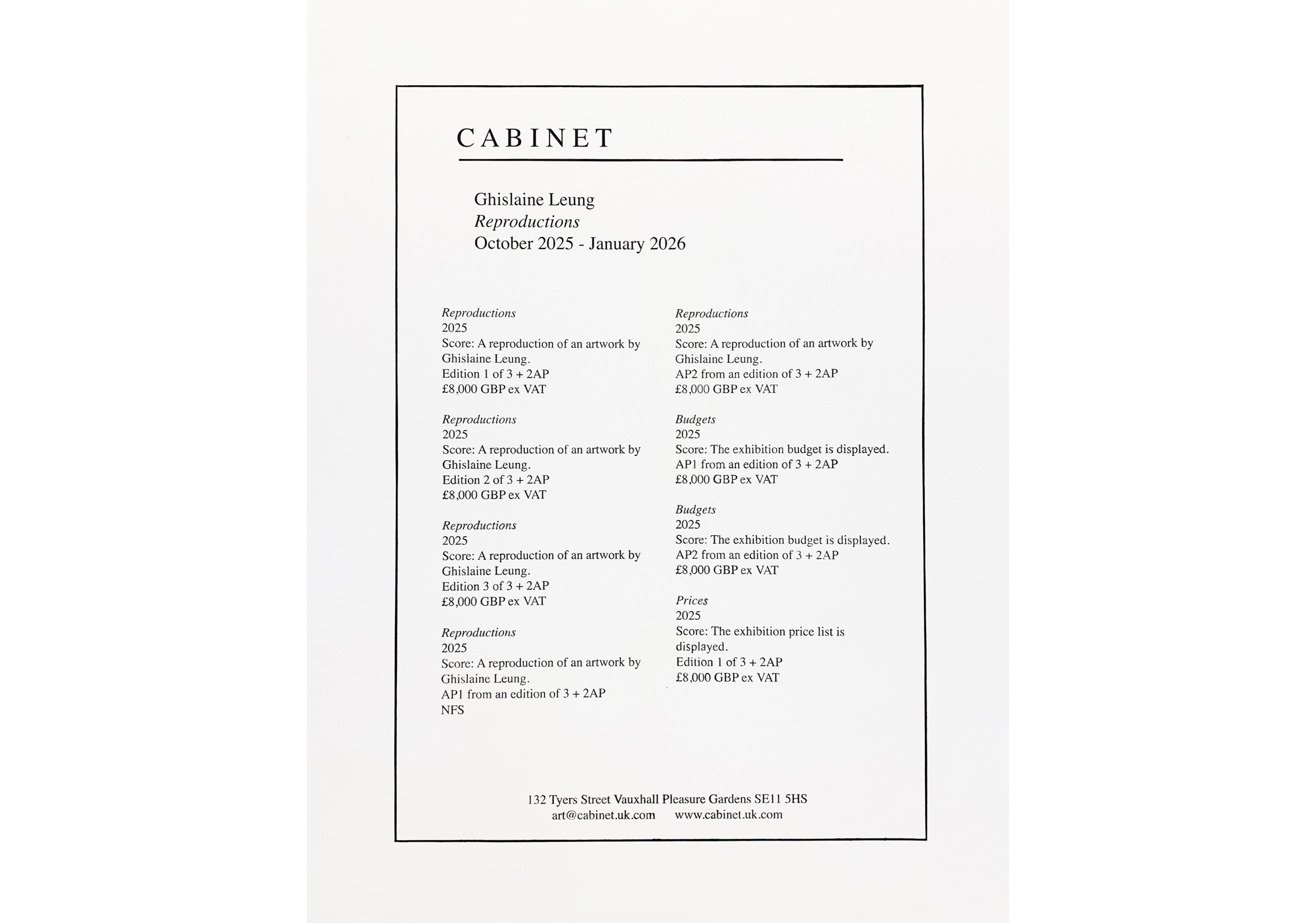

Reproductions

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

Edition 1 of 3 + 2AP

Reproductions

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

Edition 2 of 3 + 2AP

Reproductions

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

Edition 3 of 3 + 2AP

Reproductions

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

AP1 from an edition of 3 + 2AP

Reproductions

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

AP2 from an edition of 3 + 2AP

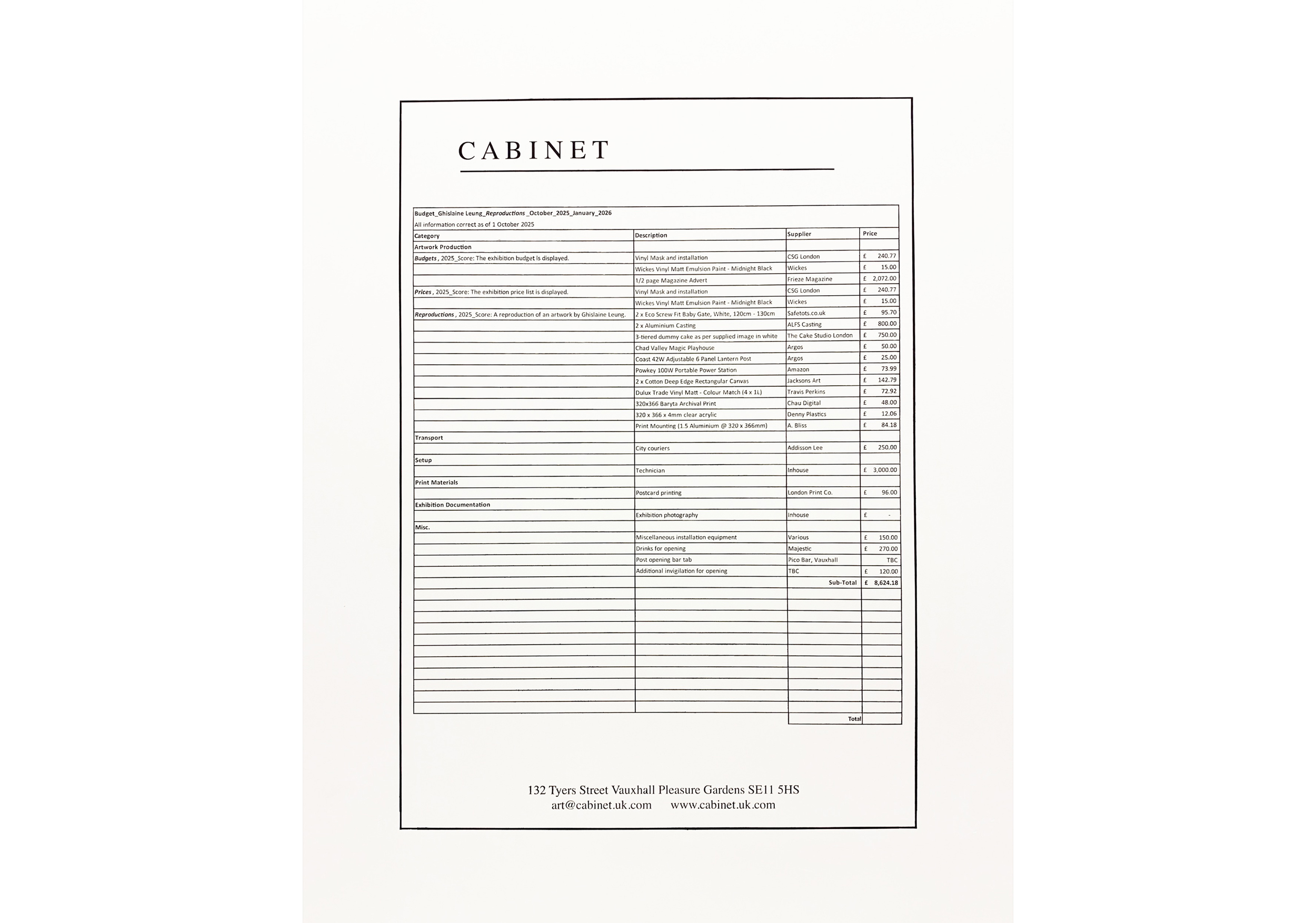

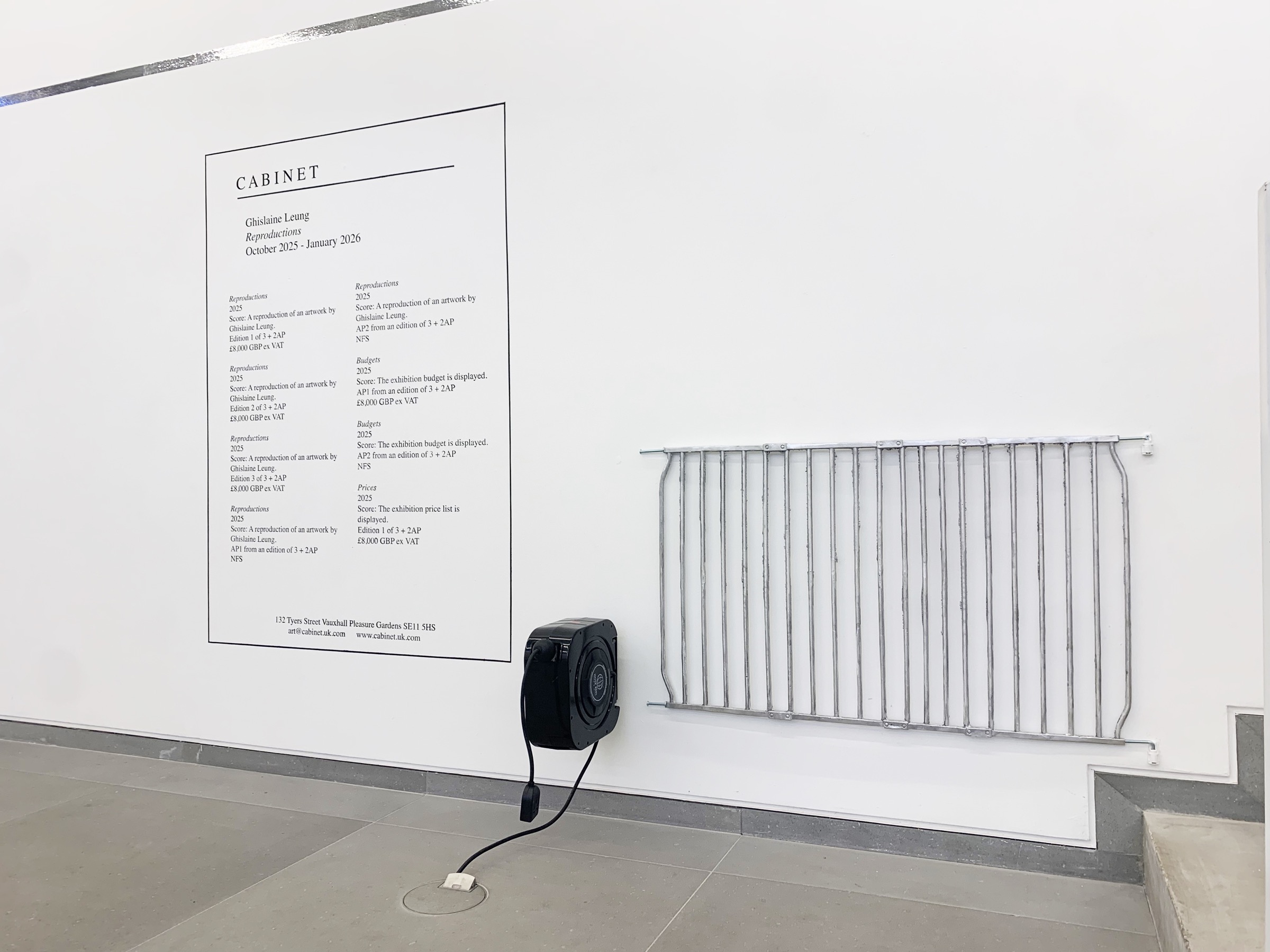

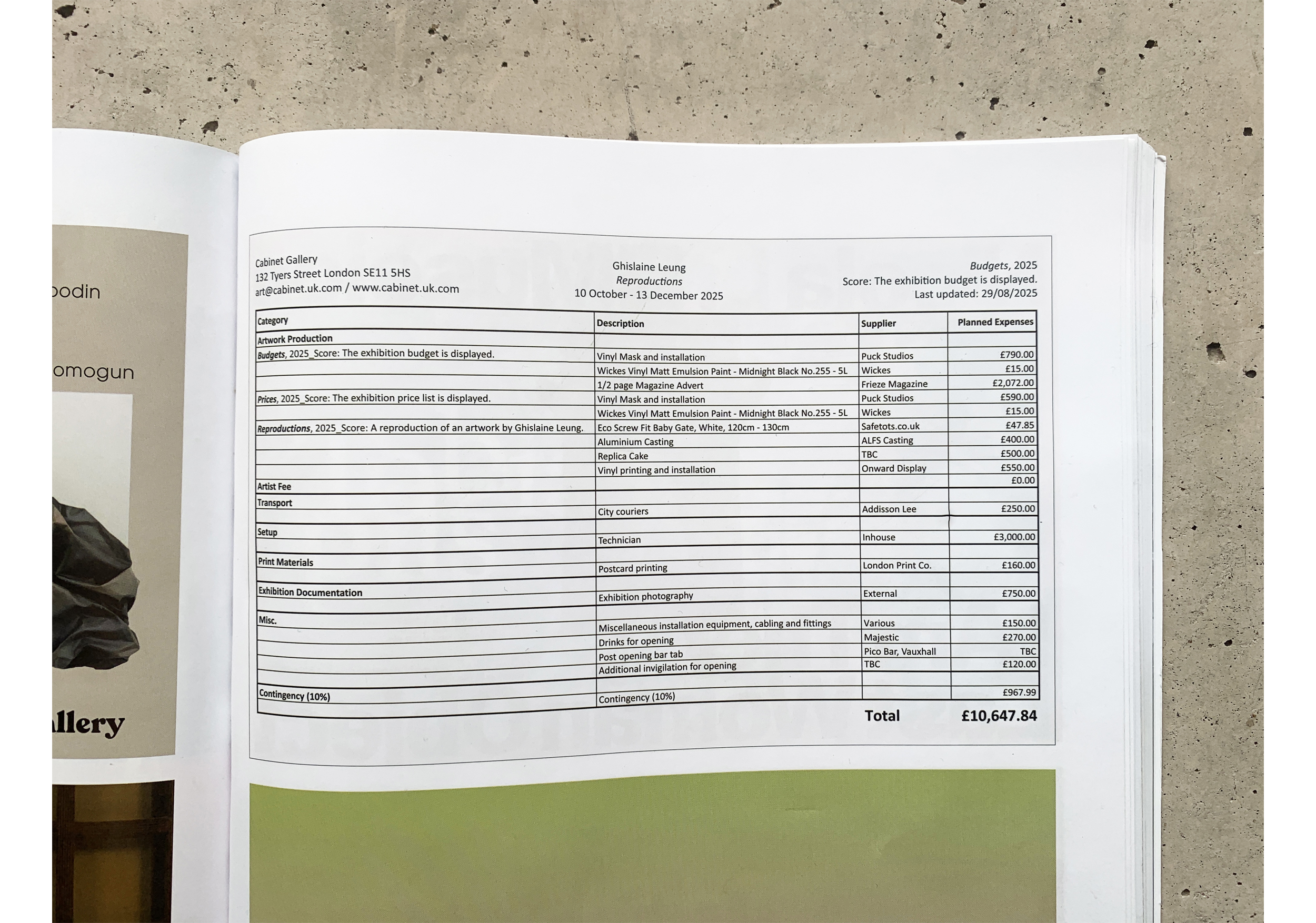

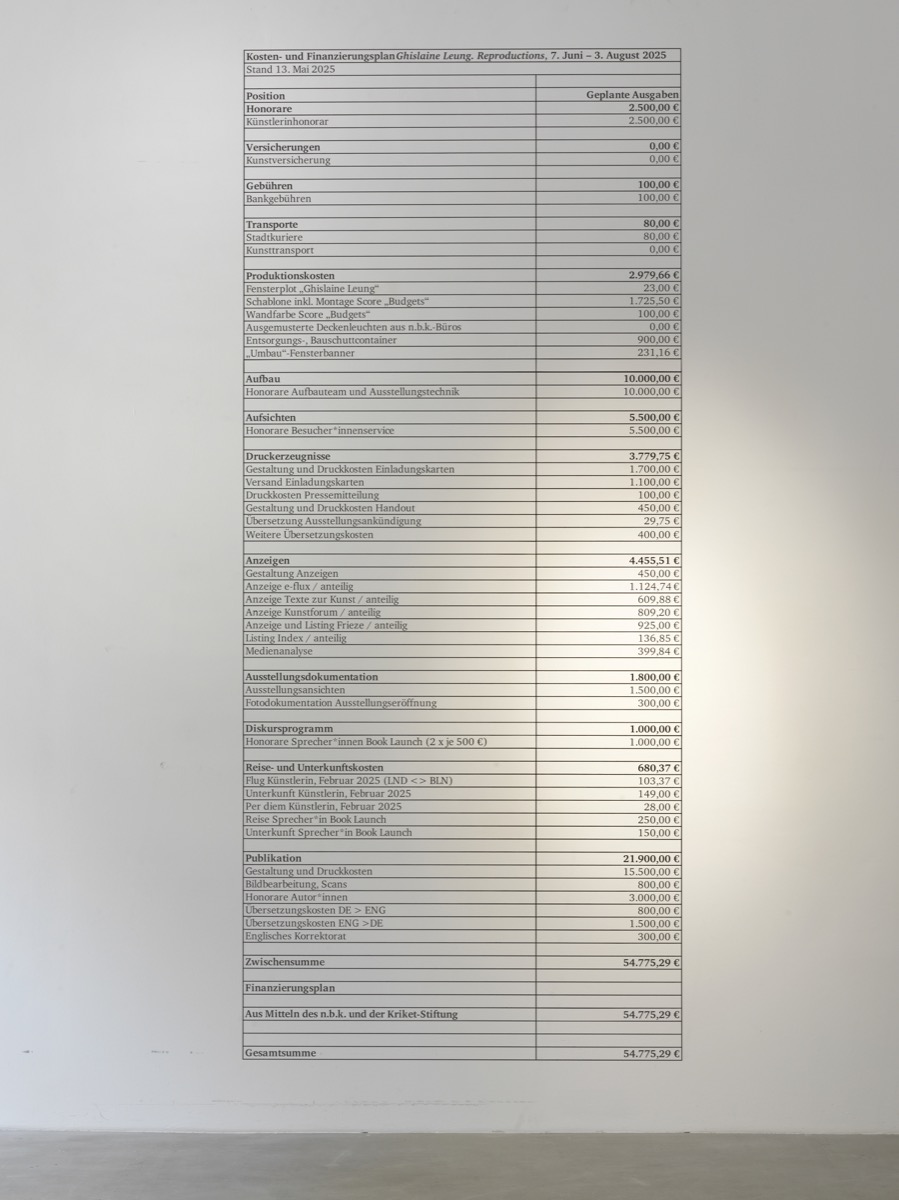

Budgets

2025

Score: The exhibition budget is displayed.

AP1 from an edition of 3 + 2AP

Budgets

2025

Score: The exhibition budget is displayed.

AP2 from an edition of 3 + 2AP

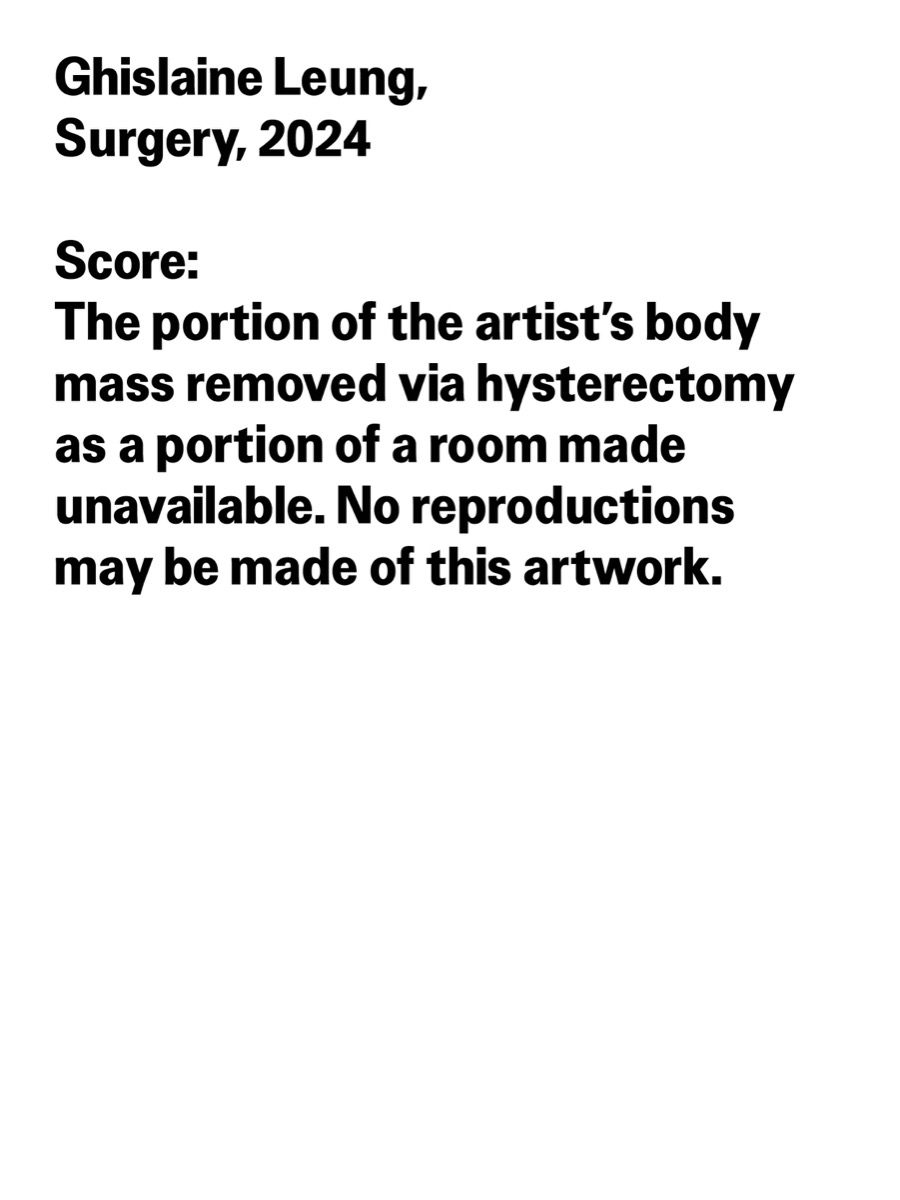

Prices

2025

Score: The exhibition price list is displayed.

Edition 1 of 3 + 2AP

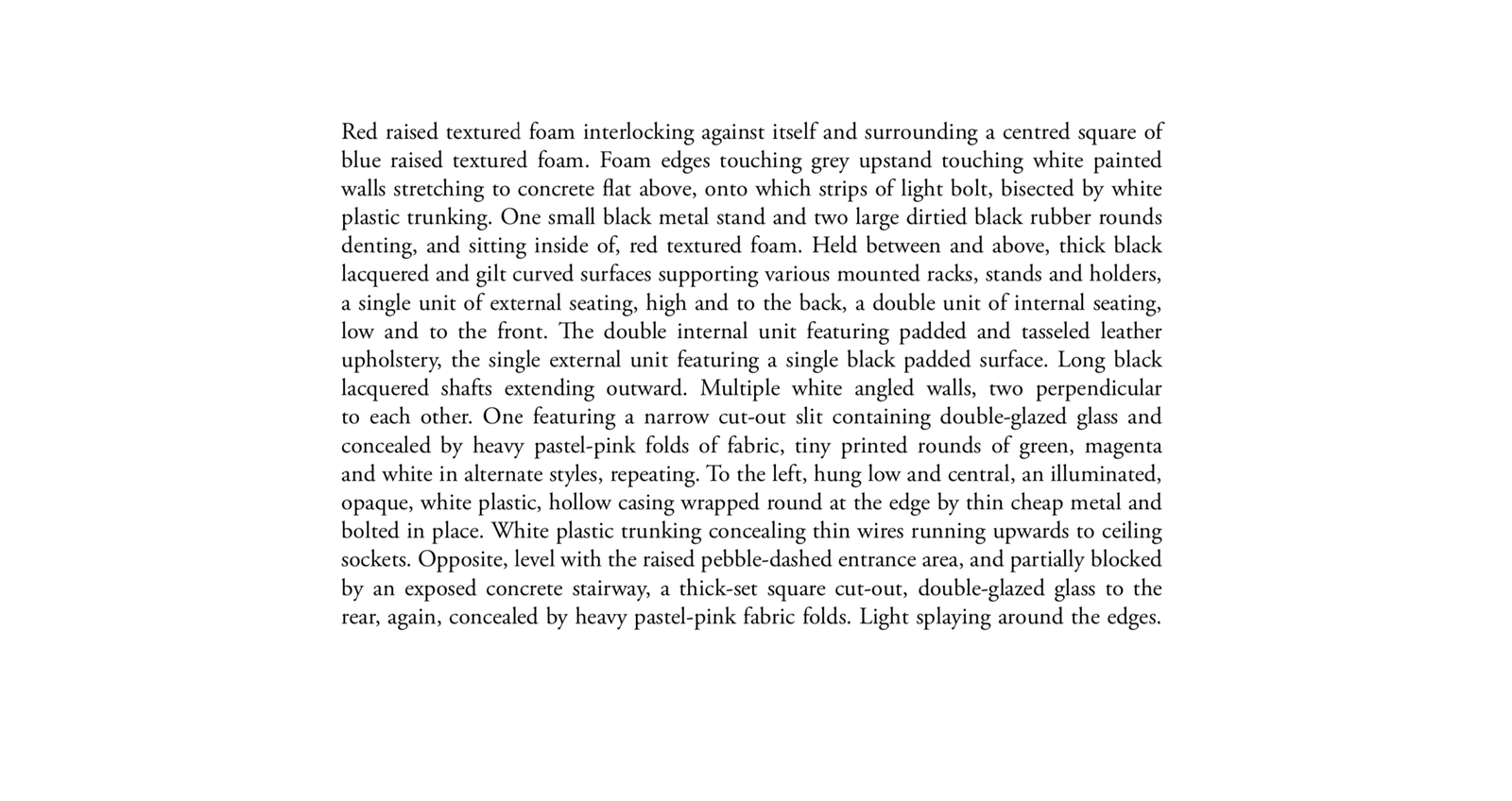

For over ten years Leung has worked predominately with scores, short written descriptions interpreted by the exhibitor, and dependent on the architectural, structural and social context of the exhibition. As standard there are no objects assigned to the scores, and each instantiation of the work is different, there being no set precedent beyond the score itself. As artworks, the scores’ permanence lies not in their fixity as objects but their cyclical ability to be reproduced, reproduced in variation, and perpetuity. For Leung, engagement in this vulnerability and volatility of the work, came not only from a formal inquiry but very real material limitations and concerns. Scores allowed Leung to reckon with the contemporary conditions of artistic production - to work without studio, storage or shipping, to avoid the expense and exhaustion of travelling, mostly unpaid, to oversee every installation and exhibition. It is perhaps this defiance, her refusal to prioritise productivity and control over all else, her attempt to live limits inclusive, that defines much of Leung’s art. Her scores constitute a way, not only to make art, but to continue to be able to do so.

Since 2020, and the birth of her daughter, Leung’s work has shifted from not only a refusal of dominant models of productivity but an affirmation of reproductive labour in its own right. Unable to travel for install or attend her own openings, Leung had to not only allow her Scores to work harder, but reflexively shift her contextual parameters. Her works expanded to engage in her own emotional, economic material limits; the difficulties of continuing to be an artist, a mother and working multiple jobs in order to do so. Works increasingly dealt with time management, administration, maintenance, situating the work’s multivalenced identity within her own. What began as Leung’s absence became an active withdrawal, one constitutive to the work’s implementation and necessary for its production; in terms of both the Scores’ interpretation, and Leung’s ability to keep working as an artist. As demand increased Leung decreased involvement, always maintaining exhibition making but refusing many other moments of visibility. Leung rarely attends her own openings, and has no photos of herself in circulation, but remains heavily engaged in reproductive work such as teaching, talks and writing.

In the two exhibitions titled Reproductions that Leung has produced this year, the first was at n.b.k. in Berlin, the second here at Cabinet Gallery, the artist has expanded her insistence on reproductive labour even further. The works at n.b.k. specified that the gallery was left as it was from the previous show, that the exhibition budget was displayed, that items no longer in n.b.k.’s use were shown. Reproductions at Cabinet extends further to encompass the artist’s concerns with the commercial model of production. In Budgets it is noticeable that there is no artist fee, a standard procedure in commercial gallery work. The artist will only be paid if the work sells, and this is true for the gallery also. As is evident in the work Prices, the economy both artist and gallery enter into is precarious. Leung’s response to this, is to further withdraw her labour and in doing so simultaneously expand the work’s remit. Reproductions allows for a reproduction of any of Leung’s works to be shown. The objects in the gallery are not the work, they are the result of an action and labour that is. Each artwork’s appearance here is dependent on the priorities and demands of these working conditions. Burrs, bleeds and imperfections inclusive, it is the work. Like all of Leung’s works, their value lies in a refuting of those very terms, the systems that structure them, and us with them.

2025

Score: The exhibition price list is displayed.

Edition 1 of 3 + 2AP

2025

Score: The exhibition budget is displayed.

AP1 from an edition of 3 + 2AP

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

AP2 from an edition of 3 + 2AP

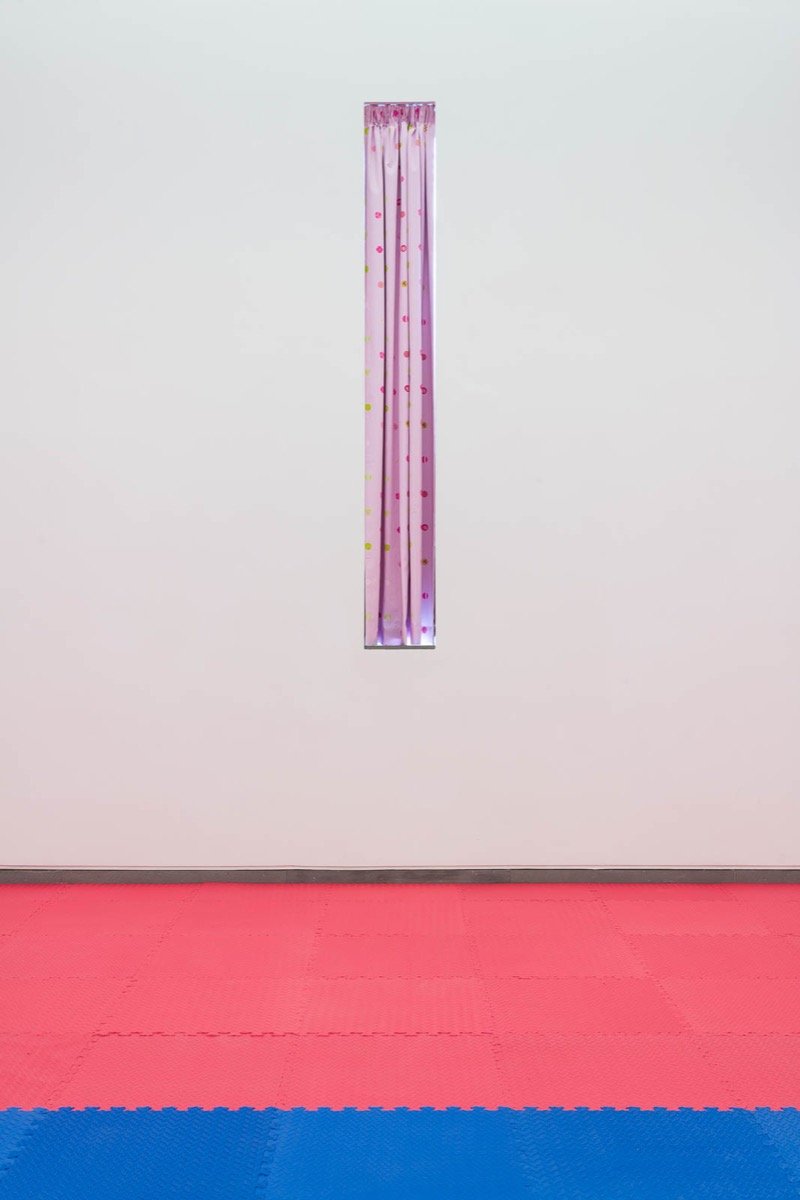

(Shown here as a reproduction of Flags, 2019

Score: All doors internal to the space painted gloss black.)

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

Edition 2 of 3 + 2AP

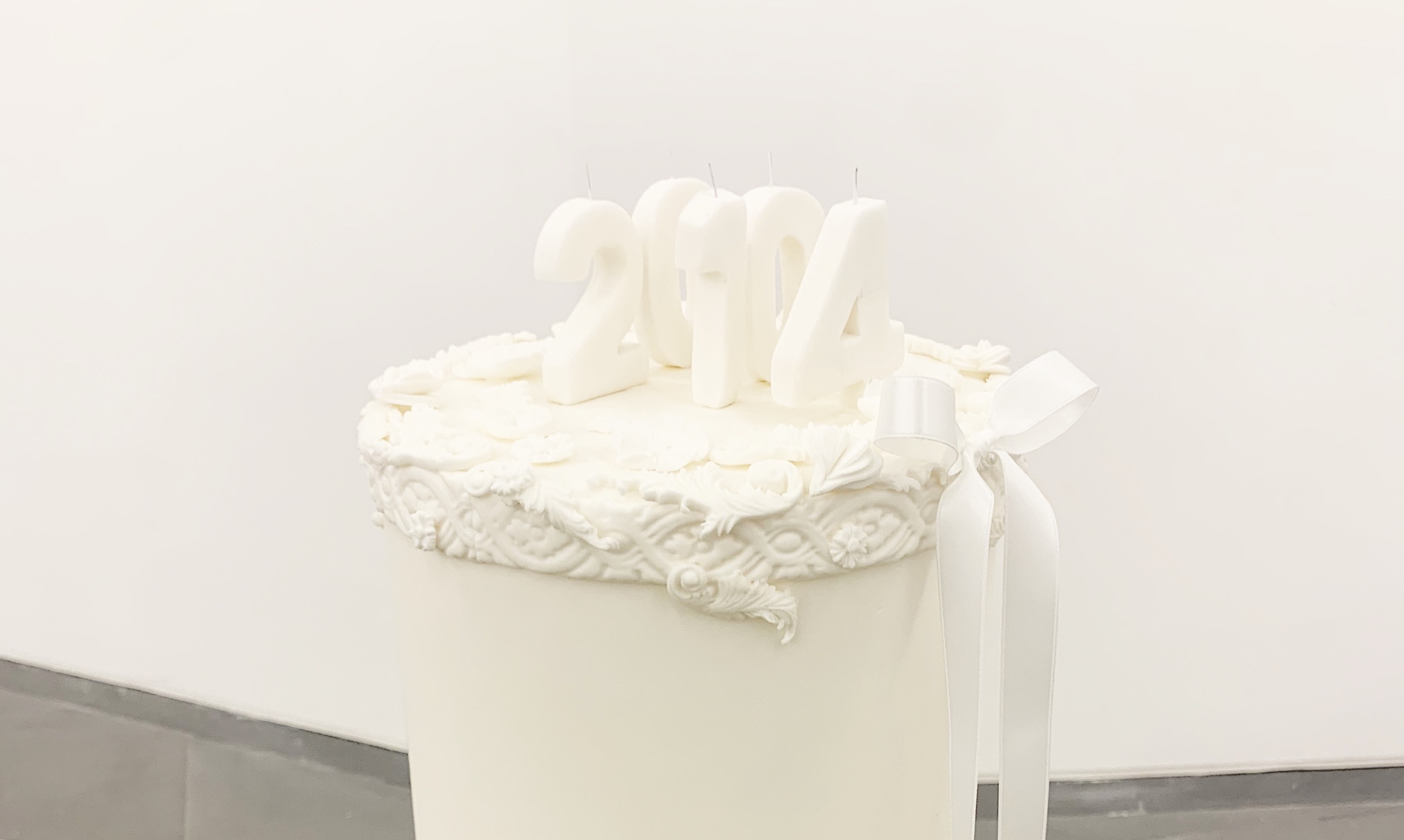

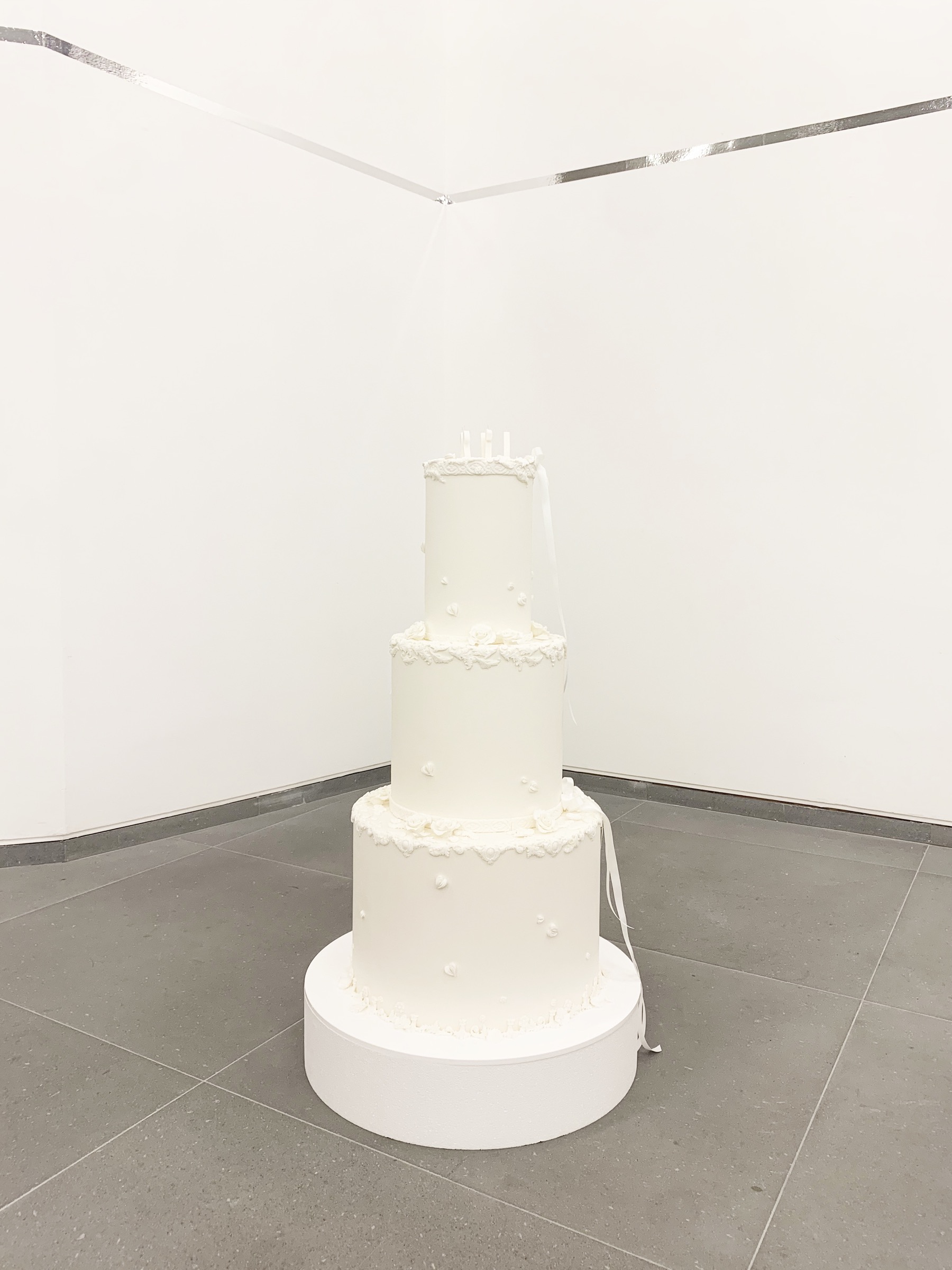

(Shown here as a reproduction of Four Years in Ten Years in Twenty Years, 2024

Score: A three-tier anniversary cake to mark four years of being a mother, ten years of being an artist, and twenty years with her partner.)

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

Edition 2 of 3 + 2AP

(Shown here as a reproduction of Four Years in Ten Years in Twenty Years, 2024

Score: A three-tier anniversary cake to mark four years of being a mother, ten years of being an artist, and twenty years with her partner.)

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

Edition 2 of 3 + 2AP

(Shown here as a reproduction of Four Years in Ten Years in Twenty Years, 2024

Score: A three-tier anniversary cake to mark four years of being a mother, ten years of being an artist, and twenty years with her partner.)

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

AP1 from an Edition of 3 + 2AP

(Shown here as a reproduction of Kingdom, 2019

Score: One scaled down lamp post, light bulb, portable battery generator and retractable extension reels.)

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

AP1 from an Edition of 3 + 2AP

(Shown here as a reproduction of Kingdom, 2019

Score: One scaled down lamp post, light bulb, portable battery generator and retractable extension reels.)

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

AP1 from an Edition of 3 + 2AP

(Shown here as a reproduction of Kingdom, 2019

Score: One scaled down lamp post, light bulb, portable battery generator and retractable extension reels.)

2025

Score: A reproduction of an artwork by Ghislaine Leung.

Edition 3 of 3 + 2AP

(Shown here as a reroduction of ____ : ____ / ____

Score: A line of metal tape across all the walls at the standard minimum ceiling height of this location. A children’s playhouse purchased from this location. The title of the work is the standard centred height of an artwork hanging on a wall in the location: standard minimum ceiling height in this location / the height of the children’s playhouse purchased in this location.)

2025

Score: The exhibition budget is displayed.

AP2 from an edition of 3 + 2AP

Frieze Magazine, October 2025, Page 31

Ghislaine Leung

Reproductions

NBK, Berlin

7 June - 3 August 2025

“It is spring. The blossom is on the trees. My daughter dances in the kitchen. Her thick hair is dark and wavy. It is beautiful. It is the same as my hair, a little lighter. I have never seen my hair this way though. I cut my hair off when I was 15. People loved my hair. They’d always comment on it, touching it. How thick and black and heavy it was. Its difference. I hated it. Being looked at. Evaluated. I cut it off, bleached it. The peroxide burning my scalp. And I felt free. For a time. I have felt ashamed as long as I remember. Of my hair, body, skin, teeth, eyes, accent, clothes. Of where I’m from, of not knowing where I’m from. Of money, having none or having some. Of working, of not working. Of not getting the right shows, of doing the wrong shows. Of not doing something, of doing something wrong. Of not being good enough, of not being enough. Always inadequate, frightened, hidden, hiding, wrong. And always so sure of this wrong, never stopping to question its right. The validity of its claim. Of rightness. That things might be upheld because it allows others to be held down. A shame that shuts us up, hollows us out. A protection that serves to hide us from each other and ourselves. It repeats at every level. Stop. Here is my removal, here is what is always removed. What is left is not nothing, it is everything. Everything that is already happening. Release. See, the sun feels good on your skin. The water is cold at first but you get used to it. Take my hand, we have everything we need already.”

- Ghislaine Leung

Score: The exhibition budget is displayed.

Maintenance, 2025

Score: The exhibition space is left as it is.

n.b.k. Edition, 2025

Objects no longer in n.b.k. use.

n.b.k. Edition, 2025

Objects no longer in n.b.k. use.

n.b.k. Edition, 2025

Objects no longer in n.b.k. use.

n.b.k. Edition, 2025

Objects no longer in n.b.k. use.

n.b.k. Edition, 2025

Objects no longer in n.b.k. use.

Ghislaine Leung

Holdings

Renaissance Society Chicago

20 January – 14 April 2024

My father disliked where he was from. He wanted to leave as soon as he knew he was there. He drew military boats and watched American films and British TV. He said he was like a 12 year old when he arrived in the UK at 20. His mother became ill when he was still at university in London, my brother only a small baby at home. He went to see her, and she died two weeks after he returned. He coughed constantly, always ill. And later, after I was born, his father refused to travel, sick himself and uncertain. And we did not travel to him, he didn’t write to us. My father was embarrassed by his father’s poor English, their small home, with nowhere for anyone to stay. Troubled by the gulf of difference between that place and his new English wife and children, his new life forged apart from this old one. The places he had lived in were no longer there, the wide waters he rowed across as a child now only small. His father and mother so proud of his achievements, the ones that took him away from them. When achievement could only mean being what you weren’t. Still, I’ll hold that absence that you gave me, I’ll love it and you. Because those who are not understood as enough, even to themselves, are, and always were, enough.

— Ghislaine Leung

A school photo of the artist in its original cardboard frame with a handwritten note on the back. The Chinese characters copied out by the artist as a child, unreadable to her then and now, translate as “To grandpapa from Ghislaine, 87.” Never sent.

Holdings, 2024

Score: An object that is no longer an artwork.

Holdings, 2024

Score: An object that is no longer an artwork.

Holdings, 2024

Score: An object that is no longer an artwork.

Holdings, 2024

Score: An object that is no longer an artwork.

Holdings, 2024

Score: An object that is no longer an artwork.

Wants, 2024

Score: A song from a film the artist’s father watched repeatedly before moving to the United Kingdom in 1970.

Hallway display cases:

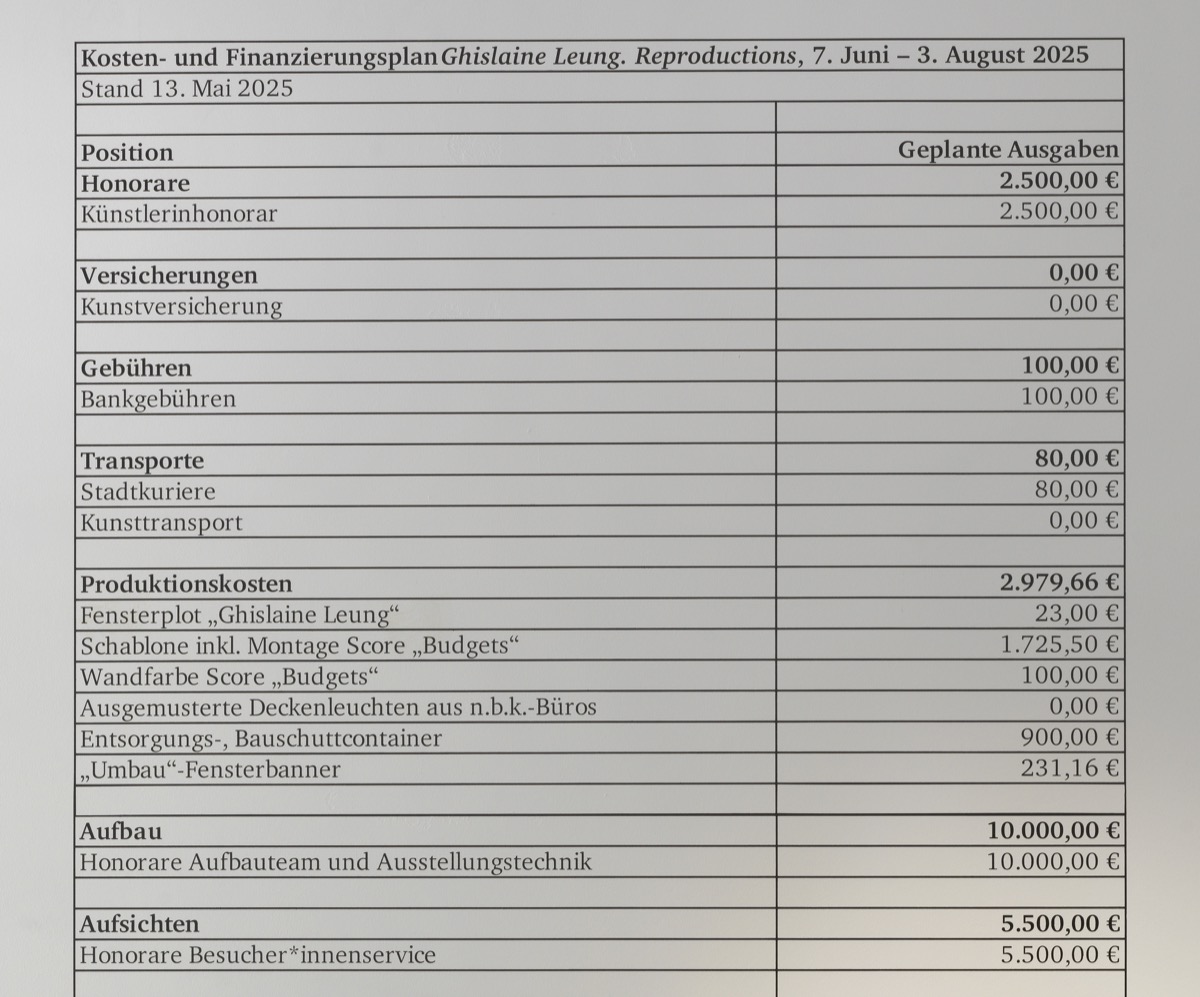

Jobs, 2024

Score: A list of jobs held by the artist.

Ghislaine Leung

Commitments

Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland

17 May - 11 August 2024

My mother was an artist. She made pencil drawings from photos and large pastel abstracts. My father was a designer, he had his own practice with a partner. They designed pens and sports equipment, water purifiers and phones—you’ve probably used some of them. We lived in a flat bought with money from the sale of the house my mother grew up in. My father had no savings or family money, and my grandmother often supported us while she was alive. My grandfather disapproved of the marriage, he did not come to my parents’ wedding. The mortgage was large and long, and the service charges on the flat were high. My mother plaited my thick black hair and smiled when people assumed I was adopted.

I drew my pictures and sat my exams.

I never corrected the pronunciation of my name. My mother’s art did not sell,and my father’s business was precarious.

He left and started to try to find teaching work elsewhere. It was hard to get, and he often worked abroad for longer and longer periods, further and further away. Holidays were not taken because we were lucky enough to be able to do the things we loved. And because we loved doing what we did, we could do it all the time. Work never stopped, in sickness or in health. Money was not talked about. Money weighed on all things. We were free. And I learnt how to be free. My daughter, still only three, looks in the bin of used toys and picks out the white doll with long blonde hair: “I want this one.”

— Ghislaine Leung

Score: A wall is equivalent to all the days in a year. The 118 days between one exhibition by the artist and the next are shown as a tomato rectangle. The 37 days the artist was on unpaid sick leave in this period due to surgery are shown inset as a tangerine square.

Care, 2024

Score: A wall is equivalent to all the days in a year. The 2016 child care hours the artist would need to cover working full time are shown as a banana rectangle. The 1140 free childcare hours supported by the UK government are shown inset as a cobalt square.

Days, 2024

Score: A wall is equivalent to all the days in a year. The 324 days between one exhibition invitation and its opening are shown as a lavender rectangle. The 25 days paid for by the artist’s exhibition fee at London Living Wage are shown inset as a basil square.

Four Years in Ten Years in Twenty Years, 2024

Score: A three-tier anniversary cake to mark four years of being a mother, ten years of being an artist, and twenty years with her partner.

Eight, 2024

Score: A large black inflatable of the number of days the artist would work for her exhibition fee of 3.000,00 CHF according to Artists’ Union England’s suggested wage rate of 41.82 GBP per hour for a lead artist. The inflatable may be inflated for eight working hours daily, for a total of eight days from the start of each exhibition period.

One Hundred and Seventy-Five, 2024

Score: A large black inflatable of the number of days the artist would work for her exhibition fee of 3.000,00 CHF according to Industria and a-n The Artists Information Company’s reported median wage in “Structurally F–cked” of 1.88 GBP per hour for an artist’s production of art- works and exhibition-making. The inflatable may be inflated for eight working hours daily, for a total of 175 days from the start of each exhibition period.

Jobs, 2024

Score: A list of jobs held by the artist.

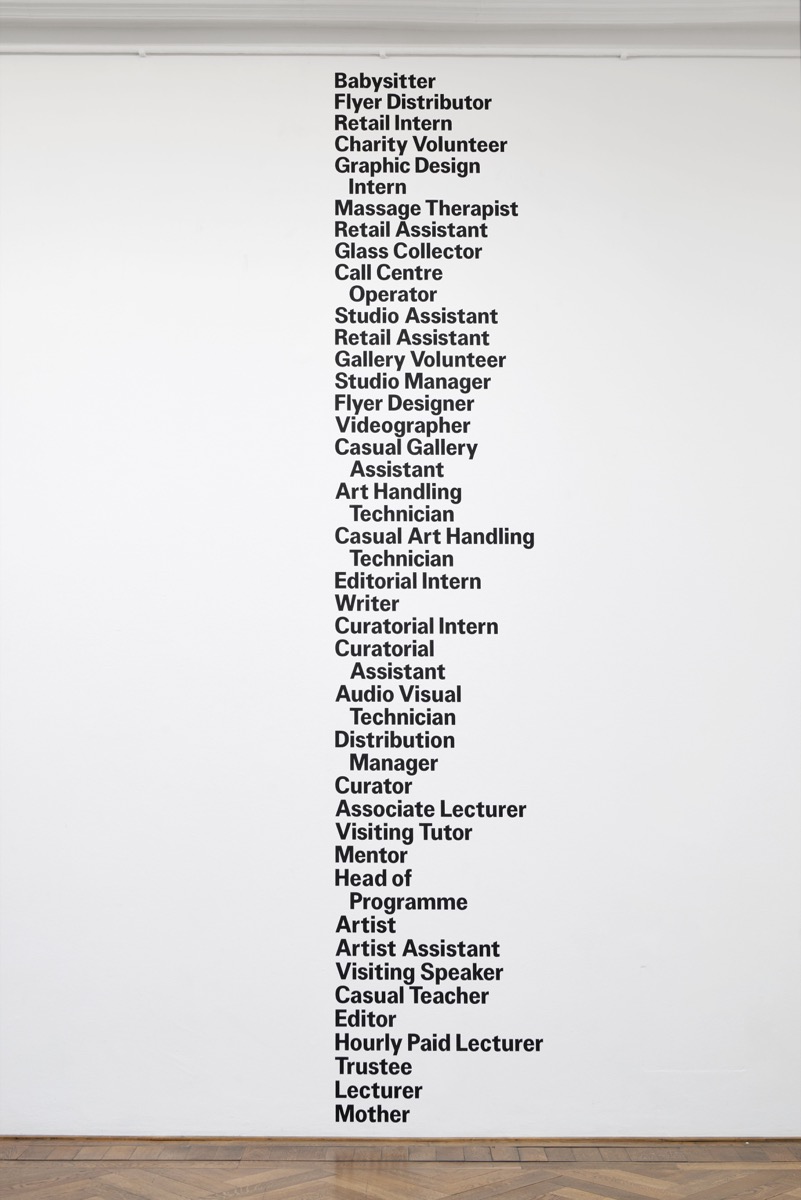

Surgery, 2024

Score: The portion of the artist’s body mass removed via hysterectomy as a portion of a room made unavailable. No reproductions may be made of this artwork.

Holdings, 2024

Score: An object that is no longer an artwork.

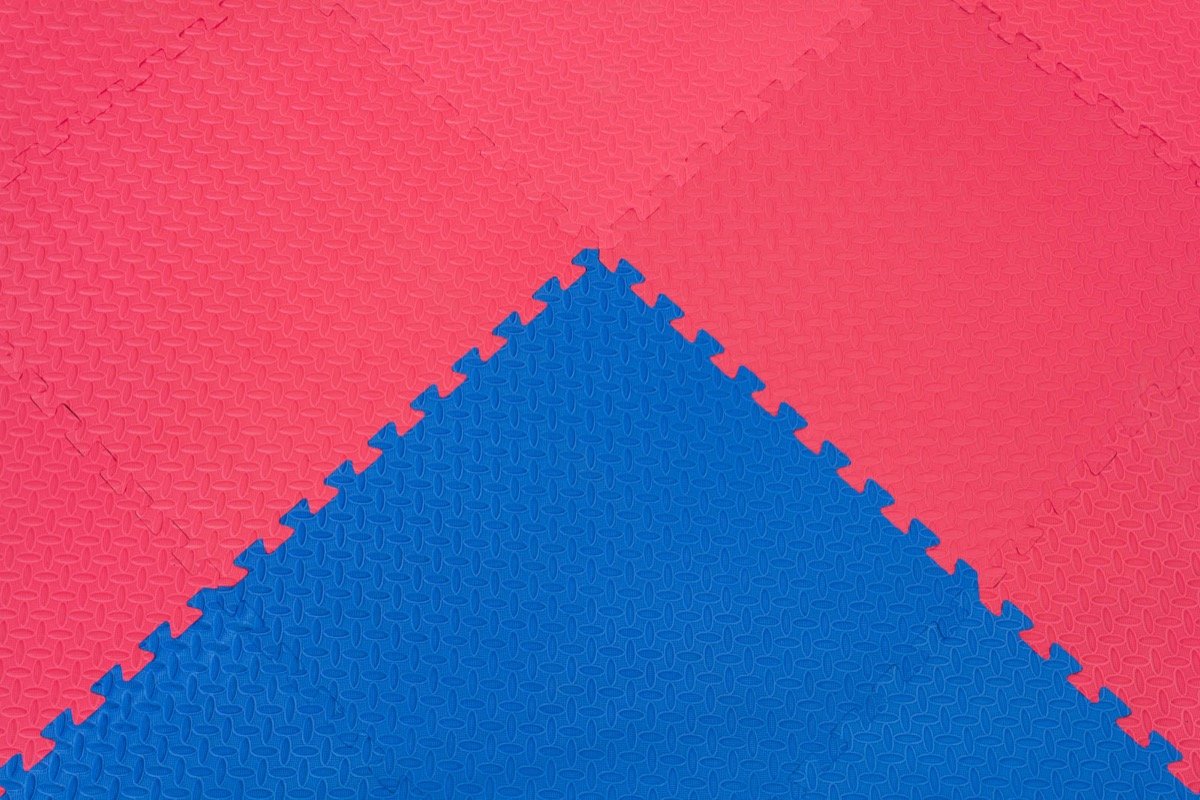

Installation Views

Ghislaine Leung

0465773005

Cabinet, London

15 April - 29 May 2021

The tiles must fill the exhibition floor area.